Sulagna Bhattacharya is a research scholar in Development Economics at IIM Calcutta. She writes about Arshi’s deeply personal journey through grief, loss, and trauma after the sudden death of her maternal aunt, a mother figure, tracing how unresolved pain evolved into clinical depression and PTSD during adolescence. This account highlights her path toward healing through therapy and advocacy, underscoring the importance of mental health awareness, coping mechanisms, and preventive healthcare in addressing silent suffering.

“It is incredibly hard to talk about her. I keep confusing which parts I am supposed to remember and which to forget. Maasi (maternal aunt), rather “Ma jaisi” (like mother) – the only person I could hug with my eyes closed and could never tell the difference whether it’s Ma or her! I remember how she would wait at the doorstep to greet us every time we visited her and pamper us with her customary luchi-torkari (puri-sabzi). Those crazy hot afternoons when we would simply lie down for a short nap on the cold mosaics of her ground-floor living room after a big, satisfying lunch with dal, specially fried masala papads, and aloo-posto (a signature dish for Bengalis involving poppy seed paste as the gravy). How the best new clothes I would receive during Durga pujas – the ones you wear on an Ashtami evening were always from her. Or the insanely long STD calls with Ma or me twice daily, updating her on every little detail – how did my math test go, which friend I had a terrible fight with, the next school function I was participating in, our dinner menu, an unending list. She berated me on multiple occasionsbut also had my back because she was my mom’s elder sister and, in a funny way, perhaps absolutely owned her. How she readily provided food and/or financial assistance to anyone in need. Or, she had this huge fun group at her yoga classes, and she couldn’t stop gloating over them! Playing around with Didi (her daughter) and two other cousins from their joint family was massive amusement – there were fake train journeys, court room dramas, hurricane attacks and Indian Idol auditions even! I waited the entire year to visit her. But most important to me was Maasi’s constant reassurance. I was an anxious child since forever, perhaps, and the possibility of the death of a loved one tremendously frightened and bothered me incessantly (the transience of life, you know), apart from the times when she comforted me, saying, ‘Don’t worry. Everything happens at the right time.’ It was a pretty believable notion for a nine-year-old, given the amount of assertion provided, except for the fact that even she did not know better.”

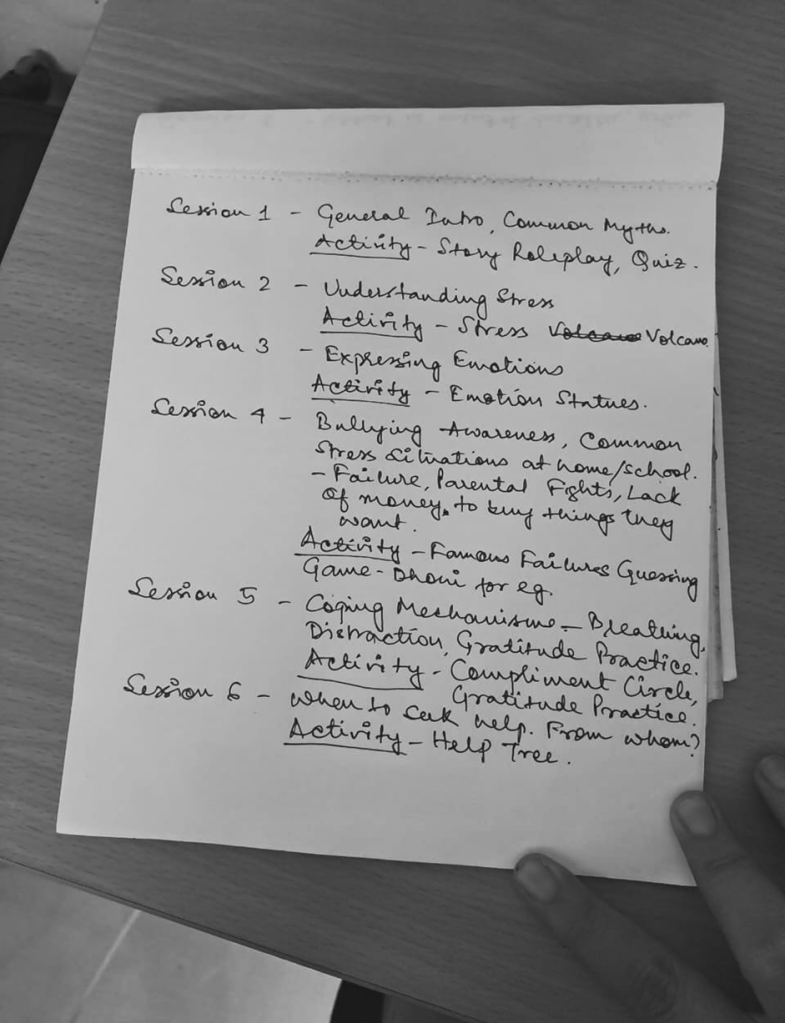

Arshi, the speaker in the above conversation, is a fellow volunteer in Bhumi, the not-for-profit organization I am currently working with. She is a Life-Skills teacher for classes 5-12 at Loreto Bowbazar Rainbow Home, a residential arrangement for children in street situations with access to basic services such as food, education, and shelter. Meanwhile, I teach English to standards one to four. Our class times coincide, and we meet every other Sunday, chatting on our long commute home. This time, she looked really excited and driven. The topic of ‘Mental Health’ was being revamped to include additional sessions in the revised Life Skills curriculum, and she already had extensive content for each extra lecture clearly chalked out in her mind. As far as I had learnt, with children, two things primarily mattered – lucidity and fun. She spoke about her plans to make classes interesting with fun activities, how that would help kids understand and express their vulnerabilities safely if they needed to – their socioeconomic conditions making them further prone to difficulties, aid in busting common myths and stigma attached to it etc with such passion, that it came across a bit strange and uncanny to an outsider like me – it’s not like you see or meet a dedicated mental health activist every other day.

Losing someone you love can leave invisible, irreversible scars on a person. A 2025 study from Nepal by Garrison et al (2025) explores how the unexpected death of a loved one can have a long-lasting impact on the mental health of an individual, especially if it occurs during their formative years. Children and teenagers run the highest risk of developing post-traumatic stress or major depression later in their lives after encountering such unanticipated event(s). While parental loss is commonly acknowledged and discussed time and again, there is much less dialogue about the grief and anguish that ensues after losing a parent-like figure or someone a child feels deeply attached to. The emotional connection is just as profound – and its void is equally catastrophic.

“So, she was gone. Apparently, everything stayed the same – the sun rose every morning, I went to school, Baba went to the office. Then Diwali arrived, we burst firecrackers and ate good food – we kept living, but something changed. It was like someone took away my normal glasses and replaced them with something black and white – there was no color. Or I couldn’t see any. I kept repeating minute details of the story of what had happened to everyone I met, burst into tears abruptly, and continued sobbing. I kept wondering where she must have gone, if it felt this terrible to me how must her daughter be dealing with it, and found myself filled with guilt – that last song she wanted to hear from me but I did not complete singing because it was 8 pm and there was an interesting episode that night I wanted to watch; that last hug and kisses I did not give her because I thought we had more time; that last answer I could have framed better when she asked what will you do if I am suddenly gone one day? The ruminations became increasingly intrusive until all I thought about and talked about was her. The flashback of Didi’s harrowing wails and screams, “Ma, Ma wake up” (when she was not in her complete senses) the evening it happened, kept growing louder and repetitive in my mind, which soon turned into nightmares, did not stop and one fine evening I realized I stayed up every night after everyone else fell asleep and went and stood by the location in our house where she had collapsed – waiting for her to return, craving to get one final glimpse of her. Obviously, she never came. I knew it was irrational, I could not discuss my behaviour with anyone for fear of being laughed at or worse, considered a “psycho”.

It took a great deal of willpower to break that habit. I started being hyper vigilant and praying every time my parents left home for groceries, work, or a doctor’s visit, because I doubted they might not return alive. My anxiety went through the roof when they accidentally missed a call while outside with me, imagining the worst possible scenarios in my mind, bargaining weird truces with God in return for their safety and longevity and feeling the panic paralyze me till the doorbell rang, until they were home. I cried myself to sleep every night, replaying the incident over and over again, thinking about what could have been done differently to prevent this, what I could have done differently to stop this from happening. A major part of me felt completely heartbroken and betrayed by how she could lie to me. Why did her reassurance, the person I believed more than anyone, perhaps, backfire so badly? The answers did not match, the puzzle turned out to have many wrong pieces, and my idea of the world around me shattered into unrecognizable crumbs – if people were meant to die abruptly at any given age or point of time, how was this world supposed to operate? It didn’t make sense at all and kept bothering me. Whenever anyone asked how old she was when she died, I would reply ‘fifty’ and listen to that disappointingly long sigh over and over again. School, music, and friends – nothing made me happy anymore. Given the amount of love, attention, respect, tears she got after her death, a tiny part inside me also wanted to die – all of this praise, attention, everyone suddenly missing you was bound to feel good, at least better than what I felt at that moment. Only if I was visible, only if someone understood. However, surprisingly, I did fairly well in my studies and apart from my sudden, rude and irritable outbursts at home, no one noticed a thing. And then I understood why.”

The DSM-5-TR (Garrison et al., 2025) provides the latest diagnostic guidelines followed by psychiatrists worldwide to help determine mental illnesses. It lists nine core symptoms with anything greater than equal to five symptoms persistent for at least 2 weeks is indicative of major depressive disorder namely, depressed mood, dysphoria (diminished or complete lack of interest in daily activities), insomnia or hypersomnia (too little or too much sleep), significant changes in body weight due to sudden gain or loss of appetite, reduced ability to think or concentrate, fatigue, psychomotor imbalances (restlessness, slowed speech or walking), feelings of worthlessness/guilt and recurrent thoughts of death. Given the hormonal upheaval teenagers go through during their puberty, it gets even harder to distinguish depression symptoms from social withdrawal/awkwardness, concentration difficulties, etc., during peak adolescence. Post traumatic stress disorder has slightly different criteria with exposure to trauma and subsequently recurrent and involuntary intrusive thoughts, avoidance of feelings or external reminders related to the trauma, ongoing negative emotional state (fear, anger, guilt, shame) along with alterations in behavior and reactivity such as aggressiveness, sleep disturbances or hyper alertness with one or two symptoms from each category lasting more than a month.

“For one thing, I was an awkward teenager, but mainly because my mom fell really ill. She could not eat, sleep or talk to anyone properly. Her only elder sister, who was like a second mother to her, just died, and she did not get a chance to say goodbye. She was not able to attend her funeral or see her one last time after she died. She was so sick and unable to deal with the reality of what was going on, it was difficult for anyone to notice what I was going through. Somehow in comparison, my pain always felt smaller compared to Ma’s or my Didi’s . So, I never expressed it and cried only in private. I was told not to irritate or anger Ma since she was already suffering from hypertension, not to wake her up while she slept, and not to bring up any topic related to Maasi that might affect her in an unexpected manner. Although she had put on a brave front in the beginning, her breakdown was even worse to observe. The diagnosis came in later. She was ‘clinically depressed’, which was all I was able to recall now. I had no idea what to do to ease her agony and mine, but Ma withdrew herself completely from everything. She would sit blankly in front of the TV for hours, silently weeping the majority of the time. We stopped attending parties and social events, avoiding distressing phone calls from relatives to acknowledge what a fateful event had occurred with us, in an attempt not to pressure her to behave ‘normally’ and be happy until she was ready, and this continued for months. She would have severe panic attacks if we went outside on a trip or if she read something triggering in the newspaper. We carried a bag with emergency medicines to every place we went since the panic attacks came absolutely out of nowhere, and I was mindful to pack accordingly. All I knew was to ensure she ate properly, took her medications on time and got adequate rest. I took my caregiving responsibilities quite seriously since it made me feel important. Visible. My symptoms, anxiety, and quality of thoughts did not improve, but Maasi quietly faded away in the background, which was then replaced by fearful thoughts of losing Ma or Baba. I shoved her somewhere deep down and threw away the key after locking it. I still keep getting dreams of losing my family members every now and then, but it is definitely a lot better than before.”

At this point, I was filled with questions – how did Maasi die, what exactly happened, did she seek professional help? However, privacy invasion was not my agenda, so I chose to remain silent. After a long pause, she finally opened up.

“Maasi had come to our house for a visit. She was fine. We giggled and had dinner later that night. It was a Saturday morning, and I had an extra class. I remember waking up early for school and watching her peacefully sleep. I somehow managed to control this extreme urge to cuddle her because of how cute and innocent she looked, but I decided against it, fearing I would ruin her deep slumber. I figured I would give her all the leftover hugs and kisses once I returned home from school. I came home, and she was gone. I never saw her again. She had had multiple cerebral attacks that morning at our house while I was in school, and was taken to a nearby hospital, which failed to cater to the ‘golden hour’ urgency commonly known to be lifesaving in such cases. She slipped into a coma, and the doctors dreaded whether she would make it to the next day. She battled for almost a month in a Kolkata hospital on ventilation and then passed away. Ma fell ill after seeing her in such a state, with tubes attached all over, so we were unable to see her before her final rites. The seniors in the house recommended not taking me to the hospital so that her smiling, happy image stayed in my mind forever, but it had its own set of pros and cons. As far as I was concerned, I regretted not waking her up that morning, not hugging her when I had the chance, not telling her how much I loved her when she was still there. There was no closure. A living being just vanished in the blink of an eye. With no warning. My suppressed feelings could no longer be contained after I started scoring poorly in class 11. I have just failed a physics class test for the first time in my life. It was a class test, one subject, just one mark short of passing, but suddenly all hell broke loose, completely exposing a bare, garbled, unprocessed version of grief that had been piling up inside me for the past two years, and I couldn’t go on anymore. The anguish felt too heavy to be carried forward. To even wake up, get out of bed or gulp food down my throat. I had no idea how to cope with this huge wave of pain and agony I was drowning in. Neither did my parents. I felt like sinking deeper and deeper into a well without anyone realizing I was in there in the first place. Neither could anyone hear me now, nor bother to check in the well searching for me. For all I knew, they were unaware such a well even existed. You probably can’t overcome such trauma without professional help. There was no choice left, I had to consult one. I suffered from both MDD and PTSD. For years. It’s still a lot of effort, but medications, therapy, journalling, and physical exercise finally worked out quite well for me.”

Coping strategies play a key role in deciding if a mental crisis can be averted. These techniques can be broadly categorized into three categories: Active Coping, Affective Coping, and Repressive/Avoidant Coping (Fisher et al., 2020). While active coping methods focus on directly addressing the problem and taking steps to solve it, affective or emotional coping helps one deal with the emotions associated with using acceptance, humor, or positive reframing. Repressive coping processes, such as denial or distraction, usually aggravate negative mental health outcomes but also have been associated with lower grief severity in certain cases. She might not have gotten the chance to process or cope, perhaps in the face of bigger consecutive crises waiting in line. But my heart sank to even think what a worse turn it could have taken because, without proper guidance, most often individuals resort to unhealthy coping mechanisms such as substance abuse or deliberate self-harm techniques to temporarily relieve the agony, which complicates the situation further.

She pauses and adds, “…to think of it now, there were warning signs which we ignored due to lack of awareness. She was a chronic hypertension patient who had frequent headaches and had bled unusually for the first time post menopause, a few days before the attack, but was dismissed as having hemorrhoids. Had we checked her blood pressure in any nearby pharmacy that day, we might have identified something and immediately sought treatment, since that was the first attack What happened 3 days later went beyond everyone’s control. Preventive healthcare is such a joke in this country. Although I have learnt my lesson, no one else seems to take it seriously. I have been called paranoid a couple of times for freaking out and catastrophizing every ailment, but I keep pushing for it. You never know when a person might actually need it. Just a simple push to go and check with the doctor can literally save your life.”

One final question I couldn’t resist asking that day – How did she get closure then?

“I did not. For a really long time. I would stand and stare at the shoes she wore when she visited our home the last time. Ma had carefully wrapped it in plastic and kept it as a memento. I remember holding her red-bordered white tant saree close to my heart and asking God why she had to leave so soon. I avoided going to their house for a long time because her pictures hanging in every room with a garland on it tormented me. Then, finally, around her tenth death anniversary, I had a dream in which she asked for water. We called our family pandit, and I performed her Shraddh ceremony after discussing it with my therapist. I just felt I needed to do this. It helped me realize why such post-death rituals exist. They are specifically designed to provide closure to the grieving family. And I think I finally got mine.”

I was so engrossed in the story that by the time it ended, her slightly strained smile and nonchalant attitude seemed oxymoronic to me. It struck me how someone could talk so objectively about these things without choking or eyes welling up, even for once, to a stranger, that too on a bus ride? What about all the mocking and judgment she might have had to face over time from her relatives, friends, family, and coworkers? (Relative to her Didi’s sorrow, how did her hurt suddenly become bigger and unmanageable to such an extent?) Was that even possible? It didn’t quite add up. I quietly inferred maybe she was too sensitive or an exception, but the odds that it could happen to any child, or even anyone, baffled me. She probably apprehended my dilemma as I stood dumbfounded at the bus stop, looked at me and said,

“Unless you can master your illness, accept your flawed self and the stigma associated with it, you cannot really help others going through it… ‘cause it is about them now, and not about your pain getting validated. Not anymore.

So, it wasn’t a choice. It was a must-do in ‘Healing 101’, perhaps.

“And yeah, as a matter of fact, it is more common than you think.”

Disclaimer: This is a personal survivor account of grief and mental health experiences. It is not intended as professional advice or a clinical guide to coping mechanisms or therapeutic interventions.

REFERENCES

Garrison-Desany, H. M., Lee, Y. H., Benjet, C., O’Connor, M., Ghimire, D. J., Smoller, J. W., … & Denckla, C. A. (2025). The unexpected death of a loved one and risk for onset of PTSD and depression in the Nepal Chitwan Valley Family Study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 120522.

Fisher, J. E., Zhou, J., Zuleta, R. F., Fullerton, C. S., Ursano, R. J., & Cozza, S. J. (2020). Coping strategies and considering the possibility of death in those bereaved by sudden and violent deaths: Grief severity, depression, and posttraumatic growth. Frontiers in psychiatry, 11, 749.

Leave a comment