The Dawn of Aspirations: Early Life of Rajani Di

Rajani Di had been the brightest student in the family. She was far more academically inclined than her brothers, loved going to school, excelled in Mathematics, and wanted to work on her English. She would receive prizes every year for her performance in the annual examination from the local chapter of the Ramkrishna Mission, that has worked with her school to encourage student performances.

As it is known, the concept of social capital of Bourdieu implies social position, obligation, and trust, helps individuals to position themselves better and the social connection, “consciously or unconsciously aimed at establishing or reproducing relationships that are directly usable in the short or long term” (Bourdieu, 1986 in Smart, 1993). Although academically sound, Rajani Di did not have connections to powerful or well-placed individuals who could facilitate educational opportunities. This aside, born into poverty, she found herself facing several challenges.

Then, her father began scouring the city to find a groom for her. It was much later that the man they’d been calling their father was their stepfather. He was looking for a groom twice or thrice her age, including some already married. Rajani Di, 14 at the time, already had offer from a boy in the neighborhood, Suresh, who was three or four years older. She hadn’t responded to his proposals, keeping to herself and preferring to focus on her education. However, fearing that she would be married off to a man of her father’s age, she eloped with Suresh. This was the only way she felt she could take charge of her life and make her choices. Besides, she’d already observed that some of her friends appeared to be in steady and happy relationships with boyfriends; a poor but blissful life with a young man close to her age who claimed to love her was a better prospect than being shackled to an unfamiliar older man.

Notable differences exist in parental aspirations and upbringing, shaped by factors such as socioeconomic status, educational attainment, cultural background, and geographical location. Working-class parents demand “obedience” (Zigler, 1970), while mothers seek “behavioral conformities from their children” (Duvall, 1946), as seen in the case of Rajani Di. Her father wanted to marry her off at a tender age, and her mother suppressed her maternal instincts, choosing not to meet her daughter until she became a mother.

At the tender age of fourteen, her future would be decided by the father, all set to alter her path forever. Rajani Di was horrified when she found out about the arrangement. It was like Sati, a practice long abolished, where the young girls had to sacrifice their lives for the honour of the family. While Sati may no longer be prevalent today, Rajani di was about to meet this fate. She felt that her aspirations were compromised at the altar of family obligations. She thought about her future and eloped to avoid being married to someone old enough to be her father.

Many girls in India are still forced into marriages with men much older than them, overlooking their emotional makeup. The narrative of many Rajani Di’s should change. It is time for society to recognize that every girl deserves to be treated with respect, care and dignity wherein consent reigns supreme.

Marriage and Beyond:

Suresh and his family hailed from Bihar. They’d sold off their land and settled in West Bengal: Suresh’s family in Kolkata and the extended family in Kharagpur. It was a large family, conservative in their beliefs and firmly convinced that formal education turns children disobedient. Rajani Di’s father-in-law was the only person in the family who could read and write. Everyone else was illiterate. Rajani Di would later teach Suresh to spell and sign his name.

Suresh, a very young man himself when they got married, had just joined the small family business and did not make enough money to support a wife. His family members weren’t happy he’d got married so early; his mother was upset that her son had married someone outside the community – a Bengali instead of a Bihari girl. She missed the opportunity to demand a huge sum of dowry from the bride’s family. Post-marriage, Rajani Di had to discontinue her education and found herself relegated to the kitchen. Her mother-in-law often would shout at her, beat her, feed her leftovers from the men’s plates –– and made her sleep underneath the only cot in their house. Later when she had conceived her first child, she was forced to continue household chores. She wasn’t allowed to rest and not cared for unlike the pregnant daughters of the house. Her requests would be coldly brushed off with a curt remark that being active helped women deliver naturally. In many parts of India, pregnant women return to their natal home till the birth of the child. However, as she has eloped all doors were shut on her.

Rajani Di’s marriage has not been a bed of roses, either. Her husband could not make decisions due to his paltry income. When they moved out, he’d sometimes drink and often hit her. This terrified her sons who were very young at the time. All these stopped, when Rajani di could not take it any longer and hit back her husband. That was the last time he ever touched alcohol or raised a hand to his wife. “He’s such a soft-spoken man that not even children are afraid of him”, says Rajani Di. “He wasn’t accustomed to heavy drinking, so I think the alcohol would make him violent. He was also quite close to his family, so I think he missed them as well.” She has taught Suresh to sign his name in Bengali. Suresh, for his part, has busted stereotypes unlike men in his family; he encourages his wife to be a very vocal and active participant in sports and events organized in the neighborhood; and he also recognizes she is the more intelligent and level-headed of the two and is content with following her instructions as she manages their finances and their property. “He has been accused of choosing his wife over his family”, Rajani Di says, “but he doesn’t care. I have a tendency to go overboard while pleasing people. I love to cook and I have nearly made myself ill cooking for people. I cannot say ‘no’ to anybody. My husband has made it clear to both our families that I will not be cooking for anybody unless I have help in the kitchen. My brothers have stopped requesting me to go and cook on festive occasions. I’d have to cook for around 75 people at a time.” Suresh also regrets that his wife was not able to continue her education. His sons don’t share their mother’s love for academics and have been working with Suresh since very young.

While the template of marriage is changing in the urban parts of India, marriage continues to remain abusive and a barrier to dignity for many. When Rajani Di eloped and married outside her caste and community, she never imagined to face this situation; the kitchen initially became her prison; marriage that was supposed to be a pathway to freedom instead confined her to a cage.

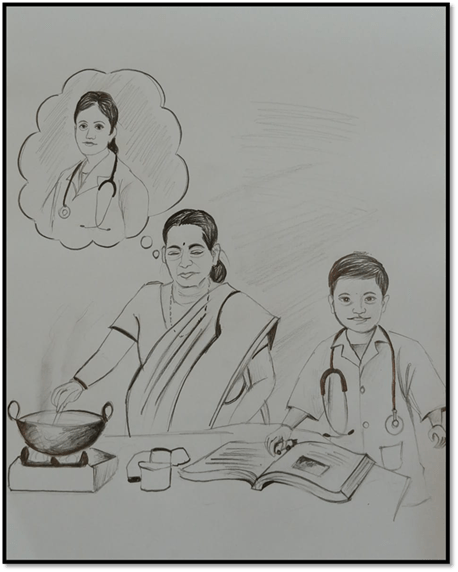

Picture Courtesy: Kingshuk Hajra

Life after Motherhood:

Rajani Di’s son, was delivered via C-section. Post-delivery her body was hemorrhaged, leaving her fragile. On knowing her fatal condition, her mother grew soft and visited the daughter for the first time in all these years.

“She wasn’t a bad mother, really!”, Rajani Di says. “She was very strict and would punish us for misbehaving. She had firm ideas about the proper ways for children to behave. I don’t know why she didn’t oppose my father’s decision to marry me off so young.”

Rajani Di had another son two years later, and moved out with her husband and children to set up their own household. Her mother-in-law blamed her for breaking up the family but Rajani Di did not wish to raise her sons in a family that did not value education, treated women as lesser beings and men were prone to alcoholism. Rajani Di’s late father-in-law and her husband’s younger brother are both prone to drinking. They set up their new residence in New Garia. Suresh took up work in a leather factory, and Rajani Di began to work as a domestic worker, initially accompanying her mother and later on her own. Years after, her dream of studying seemed to fade away. However, she decided to ignite her dreams and relive it through her sons. She enrolled her sons in school, and the eldest one joined drawing classes. Her firstborn had a penchant for art, however much to her dismay he began working right the 12th standard.

The Regrets that Matter:

Her biggest regret is the inability to continue education. She travels by train to and from work and has met several of her former teachers over the years during her journey. All of them rued that she dropped out of school and could not fulfil her dreams of becoming a doctor or a nurse. “They tell me I should have let them know as soon as my father started trying to marry me off”, says Rajani Di. “I was in a government school and my teachers could have taken up legal action to prevent my father from marrying off his underage daughter. In another of these journeys, I met one of my teachers on the train when my older son was about a year old. She told me she’d have happily let me live with her and paid for my higher education had she only known the predicament I was in at that time.” But the young, sheltered girl, barely 14 at the time of marriage, had not really been aware that help was available if she only knew how to ask for it; She only knew she wanted to get away from the men who came to ‘see’ her as the prospective bride – a practice called kone dekha among the Bengalis. “This was when the internet did not exist”, she says. “And poor homes like ours had no television. We were not as aware of our rights and responsibilities or as intelligent and resourceful as young girls these days seem to be.” In our patriarchal society, most women, till today, have had to give up their dreams to prioritize their roles as caregivers and supporters.

Does Rajani Di have any regrets? “I regret I could not study as much as I wanted to”, she says. The loss of her academic career – of her girlhood, of her dreams – comes up again and again, and, nearly 20 years later, she mourns the life she could have had but for her parents’ blatant disregard for their young daughter. “I think my mother regretted not taking a stand for me”, she says. “Before dying due to breast cancer, she bequeathed her house to me. I think she finally realized, there is no difference between a son and a daughter as both can work, fend for the family and provide care. The differences we see today – the fact that women have to struggle for basic respect, for things men take for granted because they have always had them – these are differences of opportunity created by families and by society. A woman is in no way inferior to a man.”

Intergenerational Relationships: Mother-in-Law and Daughter-in-Law:

But Rajani Di’s perception of the modern young girl as resourceful and intelligent has been, in her own words, challenged over the past year. Her older son, barely twenty, married and brought home a bride. It was a love marriage: they’d been in a short relationship, and when the girl’s parents had discovered their romantic affair, they’d turned their daughter out of the house. Parul, the bride, a few months short of turning 18, and called her boyfriend and they’d got married in a temple. Rajani Di has known Parul since she has a child and wished Parul had come to her when the parents threw her out. “I’d have convinced them to let her study and appear for her school-leaving board exam”, she says. “She could have married my son after securing a job. Now, she is a child herself, and already has a baby. She will have to wait for a long-time plan for the future.” Parul recently gave birth to a baby boy and Rajani Di has strived to be the kind of mother-in-law she has always wanted for herself: she takes care of her grandson and her daughter-in-law and encourages Parul to dress as she wishes, to participate in neighbourhood functions and to take care of herself. Parul had been a good student and a good dancer, and Rajani Di has told her to return to school and resume dance classes again once the baby grows older. “I’ve told Parul she doesn’t have to listen to anybody”, she says. “I’m very proud to have such an intelligent and accomplished daughter-in-law. She’s much more intelligent than my sons. I want her to make it big in life. We’ll support her in any way necessary.” Parul’s parents now wish to mend their fractured relationship with their daughter, but Parul prefers to stay with her husband’s family. Rajani Di and Parul have grown very close, to the point that the husbands will sometimes joke about feeling left out.

Her husband would like his daughter-in-law to study further. He also doesn’t brook any remarks or arguments about Parul. His mother once remarked on the way the young girl was dressed in Suresh’s presence. “If I had a daughter, would you have made the same comments?” Suresh had asked his mother. “She is my daughter. She’s a young girl. Please leave her alone.”

She also bemoans the absence of a daughter. She’s wanted at least one of her children to be a girl, “but that was not to be”, she says. She’d hoped for a granddaughter when Parul was pregnant, but now has a grandson. Parul is the daughter she never had.

Dreams Reborn: Fulfilling Dreams through Grandson:

Rajani Di has high hopes for her grandson. She reads rhymes to him – the same rhymes she’d learnt in the lower classes in school – and plans to get him admitted to a good school as soon as possible. “I hope he grows up to love books and academics”, she says. “I have forbidden my children from introducing him to mobile phones and to the internet. Let him read. Let him look at the world around him. Let him think.” She’ll teach him to cook, to wash to take care of the household when he’s a little older. She’ll also get him into sports and extracurriculars – singing, drawing, dancing, or anything else he might be interested in. “I want him to grow up to be accomplished”, she says. “I want to see him succeed. I want him to know how big the world is, to see and enjoy all the beauty around him”. This can be perceived as a coping mechanism, where Rajani Di finds meaning and purpose in her grandson’s successes. The story highlights the complex dynamics of family relationships, societal expectations, and individual aspirations, which is not at all new, as it is an illustration of the human experience; most people from lower socio-economic backgrounds face however, once again it raises the question of women’s position within our society. Once again, it highlights the importance of creating opportunities and a support system so that they can speak for themselves to foster a future to thrive as individuals, and not merely as “caregivers”.

A young woman, married into a family faced unimaginable torture and abuse from her parents-in-law. Despite their cruel behaviour, she continued to care for them, cooking and cleaning for the family. Her husband sometimes raised hand on her, yet she defended him, attributing his behaviour to his struggles with drinking. To support and care for her family, she took up work, sacrificing her own well-being.

In all these, the question remains does her efforts will ever be appreciated? Despite the hardships, she remained devoted to her family but is caring solely the responsibility of a woman? Isn’t it the time to dismantle traditional gender roles and work together to create a more caring and equitable world?

REFERENCES:

Duvall, E. M. (1946). Conceptions of Parenthood. American Journal of Sociology 52: 193-203. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2771063

Smart, A. (1993). Gifts, Bribes, and Guanxi: A Reconsideration of Bourdieu’s Social Capital. Cultural Anthropology, 8(3), 388–408. http://www.jstor.org/stable/656319

Zigler, E. (1970). “Social Class and the Socialization Process.” Review of Educational Research 40, no. 1: 87–110. https://doi.org/10.2307/1169578.

Author Bio:

Kaushiki

Having completed her Master’s Degree in Sociology from Presidency University, Kolkata, and qualified for UGC- NET in 2022, Kaushiki is currently pursuing her PhD in Sociology from the University of Burdwan. She is also a visiting faculty member at the Department of Sociology, St. Xavier’s College, Burdwan since 2023. She has authored several book chapters and articles, including publications in UGC-CARE-listed journals. Her research interests include the Sociology of Education, Sociology of Aging, and Sociology of Care.

Dipanwita

Dipanwita is doing her PhD from St Xavier’s College (Autonomous), Kolkata. She is also a visiting faculty member at the Department of English, St Xavier’s College, Kolkata. She has formerly worked as an Assistant Professor of English at Bharatiya Engineering Science and Technology Innovation University, Gorantla, Andhra Pradesh. Her research interests include postcolonial studies and international relations.

https://www.linkedin.com/me?trk=p_mwlite_feed-secondary_nav

#family #care #patriarchy

Leave a comment