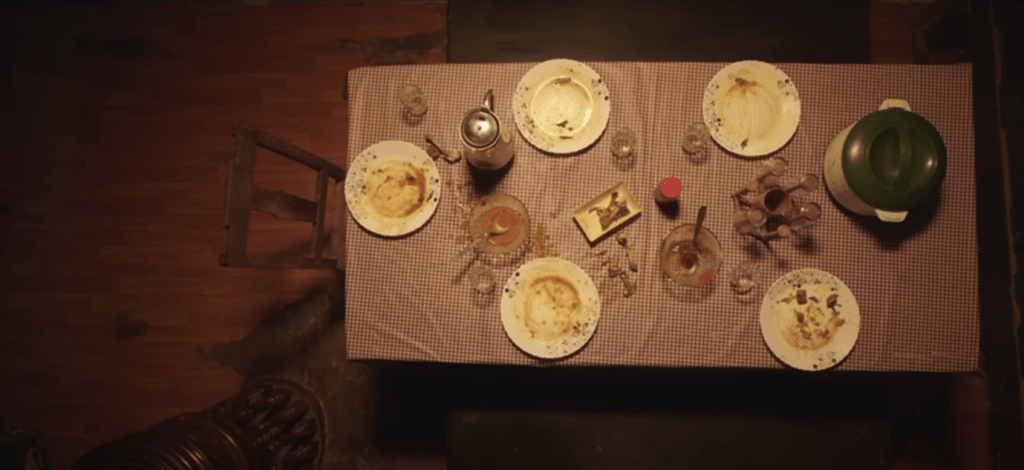

The Great Indian Kitchen, a Malayalam film directed by Jeo Baby (2021), narrates a newly wed wife’s everyday struggles within a quintessential patriarchal household. At Sabr, besides our fan-hood for the versatile Nimisha Sajayan (the wife), we recommend this film as a fine account of the politics of reproductive labor—i.e., the work that goes into reproducing and maintaining the labour force, and ensuring well-being (1).

In a scene from the movie, when the wife questions her husband about why his eating habits differ at home compared to the careful manners at a restaurant, the husband (played by Suraj Venjaramoodu) declares, “My home, my convenience; I will do as I please”. In these everyday, banal ways, men’s rules govern the household, patriarchal norms shape societal expectations and judgments of women’s duties, particularly in sustaining a family. Women are primarily responsible for all household tasks, including the endless cooking and cleaning cycles. As with other patriarchal societies, women are taught skills such as cooking and caring for children and the elderly from a young age, preparing them to become housewives (1, 2, 3). This work is an unrecognized, unpaid forms of care work that women perform – done for free, in the name of ‘love.’

The Great Indian Kitchen captures how, inside a home, the crucial care work performed by women is unacknowledged and normalized as their natural extensions of womanhood rather than work deserving of recognition and respect. It also pays attention to the extra burdens on women due to cultural and religious norms, such as the rituals related to menstruation, which view their bodies and touch as ‘unclean’ and ‘inferior’. ‘Having a woman at home is highly auspicious for the family’, exemplified by the father-in-law’s rejection of his daughter-in-law going for a job, suturing the idea that a woman’s place is strictly within the household. By depicting care work as not just about physical labour but also about the emotional toll, this film reminds us that societal expectations of women begin at home. Every detail, whether it’s the wife hurrying to fetch her husband’s toothbrush or the strict adherence to men’s dining preferences, speaks volumes about how these duties are women’s work in a system that prioritizes male convenience above all.

Household work is an inherent responsibility involving caring for a home and its members—an unspoken contract that a wife, mother, daughter, or sister must perform without pay. When daughters follow their mothers, daughters-in-law emulate their mothers-in-law, and younger sisters mirror their elder ones, a self-perpetuating cycle is created that reinforces these traditional duties and the idea that care is the quintessentially female-identified activity, leading to the prevalent label of “homemakers”.

Feminist researchers argue that homemakers are systematically exploited under capitalism because their invisibilized care work, like raising children and caring for husbands, boosts the productivity of future workers (2). Gotby, in They Call it Love, notes: “Without the labour of ensuring that most people feel well enough to keep going to work, capitalism could not function. Capitalist society produces a lot of suffering, but many people work hard to alleviate one another’s pain, stress, and boredom.”

To be cared for is the invisible substructure of autonomy, the necessary work brought about by the weakness of a human body across the span of life. Our gaze into the world is sometimes a needy one, a face that says ‘love me,’ by which it means something like ‘bring me some soup.’

– Anne Boyer, The Undying

This hidden labour, hence, is a significant contributor to social reproduction, yet its value is deliberately ignored in a capitalist system, reinforcing gender inequalities and traditional roles. The Great Indian Kitchen challenges us to reconsider how we value the unpaid care work of homemakers and to question the very foundations of what it means to be a woman. As feminist thought challenges fixed categories, it reminds us to keep this inquiry open.

References

- Gotby, Alva (2024). They Call It Love: The Politics of Emotional Life

- International Labour Organization (ILO), ‘Common Myths and Facts About Domestic Work,’

- Federici, S. (2020). Revolution at point zero: Housework, reproduction, and feminist struggle. PM press.

- England, Paula. “Emerging theories of care work.” Annu. Rev. Sociol. 31, no. 1 (2005): 381-399.

- Boyer, Anne. (2019) The undying: a meditation on modern illness. Penguin UK.

Related Reads

Menon, N. (2012). Seeing like a feminist. Penguin UK.

Baviskar, A., & Ray, R. (2020). COVID-19 at home: Gender, class, and the domestic economy in India. Feminist Studies, 46(3), 561-571.

Leave a comment